THIS REVIEW BY OLIVER HAWKINS IN THE BELL MAGAZINE SUMS UP THIS AUTOBIOGRAPHY:

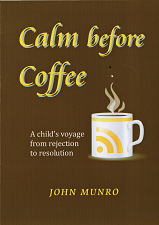

Conceived in Paris, born in New York, and raised in Surrey John Munro tells us on the back of his newly-published autobiography. All of which is true, but while most biographies are concerned with events and achievements, this one has a much more profound purpose. As John explains in a very honest opening chapter, his book is, more than anything else, an attempt to come to terms with a loveless childhood that left him not just lacking in self-confidence, but unable to form the kind of deep bonds necessary to support a fulfilled life.

The first part of the book is essentially his mother's story: an actress and artist's model, making her way from Paris to New York pregnant and unmarried and, after the birth of her son, returning crestfallen to England. Here the two great betrayals in John's life take place; firstly his mother's handing him over to a foster mother, and secondly, more damagingly, the cruelty and manipulative behaviour of this foster mother, belittling him in all manner of ways and effectively blocking any opportunities for his advancement. John's hard, early years are well described in the bleak austerity of pre-war and war-time London, and the reader will experience a real sense of relief when at last National Service with the RAF brings him release, cheerful companionship, and the warm sunshine of Egypt.

We then follow John's career in a number of advertising and

publishing, jobs, and his increasing involvement with the Moral

Re-Armament movement but, despite professional progress and strong

religious faith, John still feels blighted by his loveless upbringing.

Here he is painfully frank about his failure to commit himself to

marriage, despite numerous proposals, and the unhappiness caused to

those concerned. If the ostensible mission of John's book is to learn to

forgive his parents, there is a strong subtext of learning to forgive

himself.

A section of the book I found particularly interesting is where

John, in his Seventies, is persuaded to invent a correspondence with his

two mothers and unknown father. His letters to them are the usual

litanies of resentment and recrimination, but the responses he writes on

their behalf show objectivity and balance: his mother tells him to get

over it; his foster mother tells him how hard times were; his father

just sends him love. This willingness to see things from another's

perspective is the way forward, and much of the latter part of John's

story is entirely without rancour: his editorial work, his friendships

and activities in Arundel, his faith, and his delight in his many

godchildren. Readers of this deeply introspective 'voyage' will wish him

continuing success.

We then follow John's career in a number of advertising and

publishing, jobs, and his increasing involvement with the Moral

Re-Armament movement but, despite professional progress and strong

religious faith, John still feels blighted by his loveless upbringing.

Here he is painfully frank about his failure to commit himself to

marriage, despite numerous proposals, and the unhappiness caused to

those concerned. If the ostensible mission of John's book is to learn to

forgive his parents, there is a strong subtext of learning to forgive

himself.

A section of the book I found particularly interesting is where

John, in his Seventies, is persuaded to invent a correspondence with his

two mothers and unknown father. His letters to them are the usual

litanies of resentment and recrimination, but the responses he writes on

their behalf show objectivity and balance: his mother tells him to get

over it; his foster mother tells him how hard times were; his father

just sends him love. This willingness to see things from another's

perspective is the way forward, and much of the latter part of John's

story is entirely without rancour: his editorial work, his friendships

and activities in Arundel, his faith, and his delight in his many

godchildren. Readers of this deeply introspective 'voyage' will wish him

continuing success.

Conceived in Paris, born in New York, and raised in Surrey John Munro tells us on the back of his newly-published autobiography. All of which is true, but while most biographies are concerned with events and achievements, this one has a much more profound purpose. As John explains in a very honest opening chapter, his book is, more than anything else, an attempt to come to terms with a loveless childhood that left him not just lacking in self-confidence, but unable to form the kind of deep bonds necessary to support a fulfilled life.

The first part of the book is essentially his mother's story: an actress and artist's model, making her way from Paris to New York pregnant and unmarried and, after the birth of her son, returning crestfallen to England. Here the two great betrayals in John's life take place; firstly his mother's handing him over to a foster mother, and secondly, more damagingly, the cruelty and manipulative behaviour of this foster mother, belittling him in all manner of ways and effectively blocking any opportunities for his advancement. John's hard, early years are well described in the bleak austerity of pre-war and war-time London, and the reader will experience a real sense of relief when at last National Service with the RAF brings him release, cheerful companionship, and the warm sunshine of Egypt.

We then follow John's career in a number of advertising and

publishing, jobs, and his increasing involvement with the Moral

Re-Armament movement but, despite professional progress and strong

religious faith, John still feels blighted by his loveless upbringing.

Here he is painfully frank about his failure to commit himself to

marriage, despite numerous proposals, and the unhappiness caused to

those concerned. If the ostensible mission of John's book is to learn to

forgive his parents, there is a strong subtext of learning to forgive

himself.

A section of the book I found particularly interesting is where

John, in his Seventies, is persuaded to invent a correspondence with his

two mothers and unknown father. His letters to them are the usual

litanies of resentment and recrimination, but the responses he writes on

their behalf show objectivity and balance: his mother tells him to get

over it; his foster mother tells him how hard times were; his father

just sends him love. This willingness to see things from another's

perspective is the way forward, and much of the latter part of John's

story is entirely without rancour: his editorial work, his friendships

and activities in Arundel, his faith, and his delight in his many

godchildren. Readers of this deeply introspective 'voyage' will wish him

continuing success.

We then follow John's career in a number of advertising and

publishing, jobs, and his increasing involvement with the Moral

Re-Armament movement but, despite professional progress and strong

religious faith, John still feels blighted by his loveless upbringing.

Here he is painfully frank about his failure to commit himself to

marriage, despite numerous proposals, and the unhappiness caused to

those concerned. If the ostensible mission of John's book is to learn to

forgive his parents, there is a strong subtext of learning to forgive

himself.

A section of the book I found particularly interesting is where

John, in his Seventies, is persuaded to invent a correspondence with his

two mothers and unknown father. His letters to them are the usual

litanies of resentment and recrimination, but the responses he writes on

their behalf show objectivity and balance: his mother tells him to get

over it; his foster mother tells him how hard times were; his father

just sends him love. This willingness to see things from another's

perspective is the way forward, and much of the latter part of John's

story is entirely without rancour: his editorial work, his friendships

and activities in Arundel, his faith, and his delight in his many

godchildren. Readers of this deeply introspective 'voyage' will wish him

continuing success.www.calmbeforecoffee.com